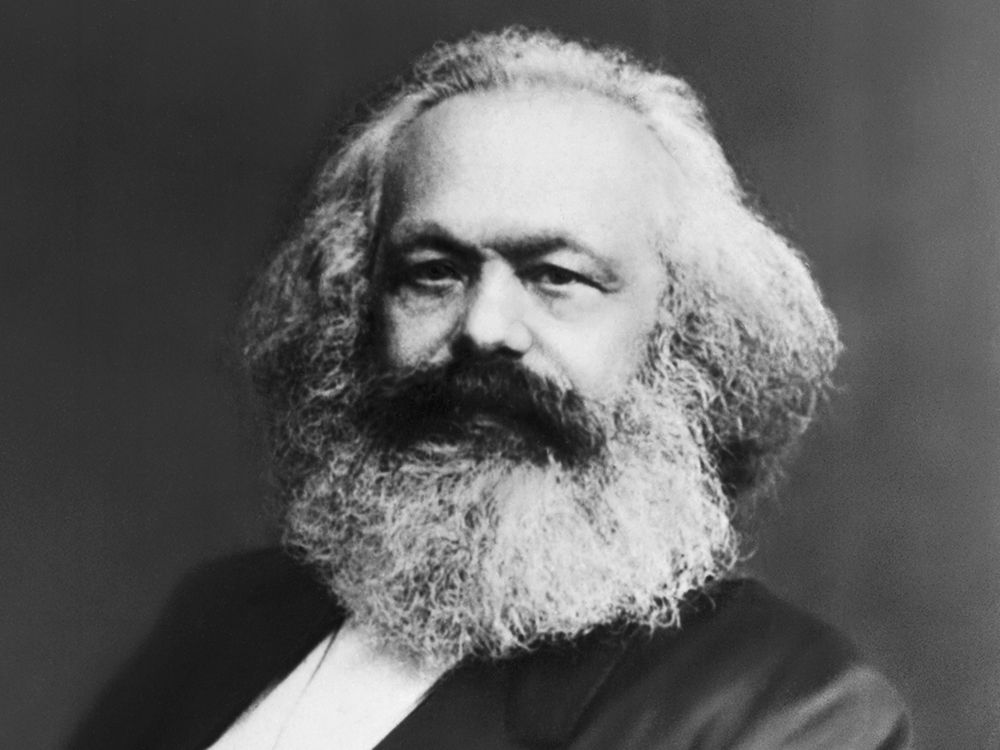

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, critic of political economy, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist and socialist revolutionary. Born in Trier, Germany, Marx studied law and philosophy at the universities of Bonn and Berlin. His best-known titles are the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto and the three-volume Das Kapital . Marx’s political and philosophical thought had an enormous influence on subsequent intellectual, economic, and political history. His name has been used as an adjective, a noun, and a school of social theory

Early Life

Karl Heinrich Marx was born on 5 May 1818 to Heinrich Marx and Henriette Pressburg. He was born at Brückengasse 664 in Trier, an ancient city then part of the Kingdom of Prussia’s Province of the Lower Rhine. Marx’s family was originally non-religious Jewish, but had converted formally to Christianity before his birth. His maternal grandfather was a Dutch rabbi, while his paternal line had supplied Trier’s rabbis since 1723, a role taken by his grandfather Meier Halevi Marx. His father, as a child known as Herschel, was the first in the line to receive a secular education. He became a lawyer with a comfortably upper middle class income and the family owned a number of Moselle vineyards, in addition to his income as an attorney. Prior to his son’s birth and after the abrogation of Jewish emancipation in the Rhineland, Herschel converted from Judaism to join the state Evangelical Church of Prussia, taking on the German forename Heinrich over the Yiddish Herschel.

Marx was educated from 1830 to 1835 at the high school in Trier. Suspected of harboring liberal teachers and pupils, the school was under police surveillance. Marx’s writings during this period exhibited a spirit of Christian devotion and a longing for self-sacrifice on behalf of humanity. In October 1835 he matriculated at the University of Bonn. The courses he attended were exclusively in the humanities, in such subjects as Greek and Roman mythology and the history of art.

Marx’s crucial experience at Berlin was his introduction to Hegel’s philosophy, regnant there, and his adherence to the Young Hegelians. At first he felt a repugnance toward Hegel’s doctrines; when Marx fell sick it was partially, as he wrote his father, “from intense vexation at having to make an idol of a view I detested.” The Hegelian pressure in the revolutionary student culture was powerful, however, and Marx joined a society called the Doctor Club, whose members were intensely involved in the new literary and philosophical movement. Their chief figure was Bruno Bauer, a young lecturer in theology, who was developing the idea that the Christian Gospels were a record not of history but of human fantasies arising from emotional needs and that Jesus had not been a historical person. Marx enrolled in a course of lectures given by Bauer on the prophet Isaiah. Bauer taught that a new social catastrophe “more tremendous” than that of the advent of Christianity was in the making. The Young Hegelians began moving rapidly toward atheism and also talked vaguely of political action.

By 1837, Marx was writing both fiction and non-fiction, having completed a short novel, Scorpion and Felix; a drama, Oulanem; as well as a number of love poems dedicated to Jenny von Westphalen. None of this early work was published during his lifetime.The love poems were published posthumously in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 1. Marx soon abandoned fiction for other pursuits, including the study of both English and Italian, art history and the translation of Latin classics. He began co-operating with Bruno Bauer on editing Hegel’s Philosophy of Religion in 1840. Marx was also engaged in writing his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature, which he completed in 1841. It was described as “a daring and original piece of work in which Marx set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy”. The essay was controversial, particularly among the conservative professors at the University of Berlin. Marx decided instead to submit his thesis to the more liberal University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him his Ph.D. in April 1841. As Marx and Bauer were both atheists, in March 1841 they began plans for a journal entitled Archiv des Atheismus (Atheistic Archives), but it never came to fruition. In July, Marx and Bauer took a trip to Bonn from Berlin. There they scandalised their class by getting drunk, laughing in church and galloping through the streets on donkeys.

In 1843, Marx became co-editor of a new, radical left-wing Parisian newspaper, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals), then being set up by the German activist Arnold Ruge to bring together German and French radicals. Therefore Marx and his wife moved to Paris in October 1843. Initially living with Ruge and his wife communally at 23 Rue Vaneau, they found the living conditions difficult, so moved out following the birth of their daughter Jenny in 1844. Although intended to attract writers from both France and the German states, the Jahrbücher was dominated by the latter and the only non-German writer was the exiled Russian anarchist collectivist Mikhail Bakunin. Marx contributed two essays to the paper, “Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right” and “On the Jewish Question”, the latter introducing his belief that the proletariat were a revolutionary force and marking his embrace of communism. Only one issue was published, but it was relatively successful, largely owing to the inclusion of Heinrich Heine’s satirical odes on King Ludwig of Bavaria, leading the German states to ban it and seize imported copies (Ruge nevertheless refused to fund the publication of further issues and his friendship with Marx broke down). After the paper’s collapse, Marx began writing for the only uncensored German-language radical newspaper left, Vorwärts! (Forward!).

During the time that he lived at 38 Rue Vaneau in Paris from October 1843 until January 1845, Marx engaged in an intensive study of political economy, the French socialists and the history of France. The study of, and critique of political economy is a project that Marx would pursue for the rest of his life and would result in his major economic work—the three-volume series called Das Kapital.

Karl Marx’s religion

His extraordinary, original vision of man’s helpless entrapment in religion has been reduced by opponents and proponents both into the one short, shabby cliché: “religion is the opium of the people”. He accorded no importance to religion except in its role as a lackey of the oppressor and a deluder of the oppressed.

He said: “The social principles of Christianity declare all the vile acts of the oppressors to be either a just punishment for original sin and other sins, or trials which the Lord, in his infinite wisdom, ordains for the redeemed.”

He states: “The foundation of irreligious criticism is: man makes religion, religion does not make man.” Because, “religion is the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet won through to himself, or has already lost himself again.” Religion is an alter ego created by man. “Man,” he clarifies, “is no abstract being squatting outside the world.

Marx concludes, “the criticism of Heaven turns into the criticism of Earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics.”

Marxism

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict as well as a dialectical perspective to view social transformation. Marxism has had a profound impact on global academia, having influenced many fields, including anthropology, archaeology, art theory, criminology, cultural studies, economics and many more.

The written work of Marx cannot be reduced to a philosophy, much less to a philosophical system. The whole of his work is a radical critique of philosophy, especially of G.W.F. Hegel’s idealist system and of the philosophies of the left and right post-Hegelians. It is not, however, a mere denial of those philosophies. Marx declared that philosophy must become reality. One could no longer be content with interpreting the world; one must be concerned with transforming it, which meant transforming both the world itself and human consciousness of it.

Karl Marx offered many classic theories to explain different aspects of society.

Books

-

Das Capital

In Das Kapital, Marx proposes that the motivating force of capitalism is in the exploitation of labor, whose unpaid work is the ultimate source of surplus value. The owner of the means of production is able to claim the right to this surplus value because they are legally protected by the ruling regime through property rights and the legally established distribution of shares which are by law distributed only to company owners and their board members.

The historical section shows how these rights were acquired in the first place chiefly through plunder and conquest and the activity of the merchant and “middle-man”. In producing capital, the workers continually reproduce the economic conditions by which they labor. Das Kapital proposes an explanation of the “laws of motion” of the capitalist economic system from its origins to its future by describing the dynamics of the accumulation of capital, the growth of wage labor, the transformation of the workplace, the concentration of capital, commercial competition, the banking system, the decline of the profit rate, land-rents, etc. The series has three volumes:

Volume I is a critical analysis of political economy.

Volume II included “The Metamorphoses of Capital and Their Circuits, The Turnover of Capital and The Reproduction and Circulation of the Aggregate Social Capital”.

Volume III included “The conversion of Surplus Value into Profit and the rate of Surplus Value into the rate of Profit, Conversion of Profit into Average Profit, The Law of the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall, Conversion of Commodity Capital and Money Capital into Commercial Capital and Money-Dealing Capital (Merchant’s Capital), Division of Profit Into Interest and Profit of Enterprise, Interest Bearing Capital, Transformation of Surplus-Profit into Ground Rent, Revenues and Their Sources”.

-

Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto summarizes Marx and Engels’ theories concerning the nature of society and politics, namely that in their own words “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. It also briefly features their ideas for how the capitalist society of the time would eventually be replaced by socialism. In the last paragraph of the Manifesto, the authors call for a “forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions”, which served as a call for communist revolutions around the world.

The Communist Manifesto is divided into a preamble and four sections, the last of these a short conclusion.

The first section of the Manifesto, “Bourgeois and Proletarians”, elucidates the materialist conception of history, that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. Societies have always taken the form of an oppressed majority exploited under the yoke of an oppressive minority.

The second section, starts by stating the relationship of conscious communists to the rest of the working class. The communists’ party will not oppose other working-class parties, but unlike them, it will express the general will and defend the common interests of the world’s proletariat as a whole, independent of all nationalities.

The third section, “Socialist and Communist Literature”, distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time—these being broadly categorised as Reactionary Socialism; Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism; and Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism.

The concluding section of the Manifesto, briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the mid-nineteenth century such as France, Switzerland, Poland and Germany, this last being “on the eve of a bourgeois revolution” and predicts that a world revolution will soon follow. It ends by declaring an alliance with the democratic socialists, boldly supporting other communist revolutions and calling for united international proletarian action—”Working Men of All Countries, Unite!”.

Conclusion

The above article shown a short note on the life of Karl Marx. His life is more than Das Capital and The communist manifesto…